When Sears sold the American dream

by Jon Gorey

(https://realestate.boston.com)

Long before you could buy a flat-pack bedroom set from IKEA and spend an afternoon sweating and swearing as you put it together at home, Americans were ordering entire houses by mail that were shipped by rail and ready for hopeful homeowners to assemble piece by piece.

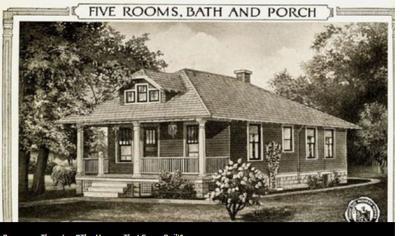

They’d pick a style and floor plan from the Sears Roebuck “Modern Homes’’ catalog and a few weeks later a boxcar would arrive at the nearest train depot with nearly everything they’d need to build a house from scratch. A typical kit might include roughly 12,000 pieces of lumber, two dozen doors, 28 windows, 240 balusters, 325 feet of crown molding, thousands of cedar shingles, 27 gallons of paint and varnish, and 750 pounds of nails, among other materials. The cost? The kits ranged from $600 to $6,000, depending on when it was sold and the floor plan.

So, if you’re flummoxed by the 64 dowels in your IKEA Hemnes dresser, imagine sorting 30,000 items with a 75-page leather-bound instruction manual.

However, the architect-designed house kits — which included Dutch Colonials, Arts and Crafts bungalows, and American Foursquares, among other styles — were popular with ambitious early 20th-century home buyers. Sears advertised that “a man of average abilities’’ could assemble one of its kit homes in about 90 days, and he’d save a bundle doing so: Centralized production and design, plus do-it-yourself labor, made Sears houses a uniquely affordable avenue to homeownership.

Sears sold about 70,000 houses from 1908 to 1940 in about 370 different styles, according to Rosemary Thornton, author of “The Houses That Sears Built.’’ And its timing couldn’t have been better. “In the early 1900s, there was a huge influx of immigrants, plus the war to end all wars ended in 1918,’’ creating a nationwide housing shortage, Thornton said.

Some of those immigrants found their piece of the American dream in a Sears Roebuck catalog. Sears began offering “easy payment’’ mortgages in 1911, Thornton said, and there were only a few questions on the application, making it remarkably fair for the era. “There was no redlining, no telling us about your ethnicity. … It was just ‘Do you have a job?’ and ‘Do you own the lot?’ ’’ Thornton said. “And if the answer to those two questions was yes, you got a mortgage.’’ A buyer who owned a lot outright could even use the land as the 25 percent down payment.

That allowed people who were often shut out of the traditional mortgage market — like women, immigrants, and people of color — to buy a home. “ ‘Progressive’ isn’t even the right word, it was ‘radical,’ ’’ Thornton said. “They threw open the door of homeownership to a very different group that otherwise might have been locked out of the market.’’

One such buyer was an immigrant German named R.W. Werners. A tailor in downtown Boston, he bought a Sears “Starlight’’ bungalow in the late 1920s to assemble in Roslindale. He chose the model with a bathroom and probably paid a bit extra for a heating system, plumbing, and electrical fixtures, all of which were add-ons offered as “good, better, or best’’ options. Werners would have had to dig out the full basement and pour his own concrete foundation (Sears didn’t ship stone or bricks). He may have hired a builder — Thornton estimates that about half of Sears home buyers did — but it’s possible he built it with the help of family and friends.

Sears wasn’t just being altruistic, though; it was a mutually beneficial arrangement. Thornton said the average Sears kit-home builder created an instant 20 percent to 30 percent equity stake — a financial cushion for both parties. Meanwhile, a big reason Sears started selling homes in the first place was to create new customers for its home goods: Homeowners bought more merchandise from its 1,200-page catalog, so encouraging homeownership was simply good business.

Almost a century after it was built, R.W. Werners’s Starlight bungalow now belongs to another middle-class immigrant family. Michael O’Dea, originally from Ireland, and his wife, Henriette, an illustrator from the Netherlands, purchased the home in 1996. They were expecting their first child and looking for a place to call home on a lean budget.

“A friend of a friend knew of this house in Roslindale — at the time I didn’t even know where Roslindale was,’’ said O’Dea, now a realtor. “The first time I stepped in there I absolutely fell in love with it.’’ It was small, under 1,000 square feet, but it felt like home — and they are raising three children in the cozy bungalow. O’Dea said his father-in-law, when visiting from Holland, would tell him, “Walking into your house is like putting on a warm jacket.’’

It also feels like walking into a catalog. The layout is mostly unchanged, and many details, from the parquet floors to the door hinges, are original. “Only four families ever owned the house as far as I know,’’ O’Dea said, “and none of them ever had enough money to muck it up.’’

O’Dea didn’t realize it was a Sears home until a few years after he’d bought it. “We were thinking about remodeling the attic, so I went to the city permitting department, and they said, ‘Oh, did you know you have a Sears-kit home?’ ’’ Sears Roebuck was listed as the architect.

In fact, many owners of Sears houses probably don’t know it. Homes change hands, new siding covers up key features, or houses get remodeled beyond recognition. Andrew Mutch, a Sears kit-house owner, blogger, and researcher, works with other enthusiasts to keep a tally of authenticated houses as they’re discovered. Mutch has documented 73 Sears-kit homes in Massachusetts to date, including O’Dea’s, but others remain hiding in plain sight. “I’m confident there are many more still to be located,’’ he said.

Thornton said there are a number of ways to tell whether your home is a Sears house, beginning with its location and when it was built. Most kit homes are within 2 miles of railroad tracks and in communities with streets named after presidents and trees. “Those are the communities developed in the 1920s,’’ Thornton said. And while Sears sold the homes for 32 years, the bulk of them were built between 1919 and 1930. So, she added, “if your house wasn’t built in that time frame, it’s not likely a Sears home. And if you’re outside of 1908 to 1940, it’s impossible.’’

One of the best indicators is stamped lumber, which you might see in the basement or attic. Framing and support beams were often stamped with a letter and number — such as “D655’’ — to simplify assembly. You can also look for shipping labels affixed to the back of millwork, such as baseboard molding or trim, or search the attic or behind the basement joists for the original blueprints or sales records.

Some architectural details can offer clues as well, such as distinctive mortise-and-tenon joinery on front porch columns or unusual five-piece triangular eave brackets. These features don’t by themselves prove that your home is a Sears house, just that it’s worth doing some research.

And because Sears financed many of its houses, mortgage records can be revealing, too. Norfolk County’s Registry of Deeds has digitized records all the way back to 1793, making it relatively easy to search for home loans issued or discharged by Sears Roebuck or one of the company’s trustees, like Walker O. Lewis, William C. Reed, Edwards D. Ford, and F.C. Schaub.

Kit houses have a small but devoted fan base, but not everyone shares that enthusiasm. O’Dea once saw a Sears house while driving around and stopped to introduce himself. “I wanted to tell the owner they had something a little bit special,’’ he said, “but she could not have cared less!’’ She might have been a renter, he said.

O’Dea said he’s seen realtors hide a Sears home’s heritage in the listing, fearing it will conjure negative connotations of “prefab’’ housing. However, while Thornton said Sears did offer a few prefabricated cottages (the walls were pre-built off-site), Sears “Honor Bilt’’ homes were constructed of premium materials and, for the most part, painstakingly assembled by hand. “The lumber was just phenomenal,’’ she said. “It was first-growth lumber on virgin forest, and we’re never going to see quality like that again.’’ The kits used Southern yellow pine for the framing, while all of the exterior components like the sheathing and trim were cypress.

What’s more, the original owners, though relative amateurs, were constructing these houses for their families. “They built them with great care and love and forethought, so they were built really well,’’ Thornton said. “People believed these houses would be handed down to their kids and to their children’s children.’’

Those houses, it turns out, may outlast Sears itself. The struggling retailer is closing more than 260 stores and selling what’s left of its good name as it tries to fend off bankruptcy, this year dealing its Craftsman tool brand to Stanley Black & Decker for $900 million. The terrible irony is that Sears, unable to keep up in an online retail environment, was the original Amazon.com — a retail juggernaut that sold nearly everything by mail and helped unify a fragmented country.

“Millions of homes that did not have any other book in common — or any books at all, other than the Bible — had the Sears catalog,’’ said Lawrence Glickman, a professor of history and American studies at Cornell University. It was for years the quintessential American company, Glickman said, and its demise would mark an important loss to our consumer culture. “Sears sold a vast range of products — including houses — but, more importantly, it sold dreams.’’

Join in and write your own page! It's easy to do. How? Simply click here to return to News portal.